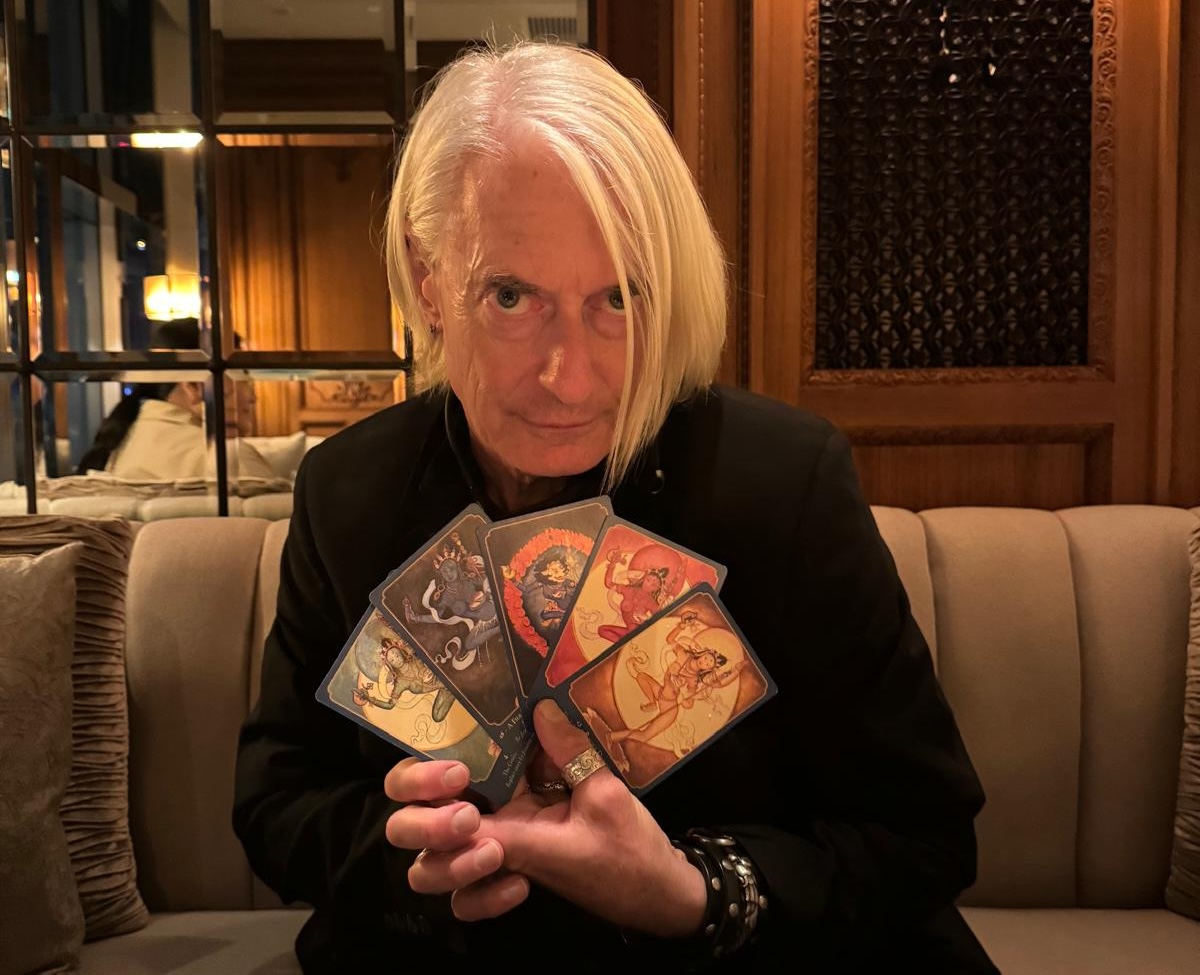

After a short trip to Chengde, I visited the hutong complex of Laurence Brahm, filmmaker, alternative music club founder, and martial arts lineage holder. He is, in fact, entrusted with bringing China to the world, and helping the world to see China. The figure in Buddhist history he admires most is Padmasambhava, or as his fans would perhaps prefer, the Lotus-born Master. The Lotus-born Master is the subject of six movies Laurence has directed and produced, each with its own story and message for the modern world.

Laurence holds a deep and abiding appreciation for all things Chinese heritage. This respect and passion shines through in his new book and movie of the same name, Gate of Nine Dragons: Searching for Kung Fu. Both the film and book were launched in Hong Kong in August. Gate of Nine Dragons is an extraordinary travelogue and biographical text infused with history and spiritual insights. There are interviews with masters that Laurence has trained under and practitioners he has learned alongside. These are interwoven with sophisticated reflections on how the martial arts are an inseparable part of Chinese and Buddhist spirituality. This is a vividly written chronicle of finding the true meaning of martial arts.

Early on in Gate of Nine Dragons, Laurence recounts what he describes as one of his most extraordinary experiences among his student days in China in the 1980s. This was his visit to the Eight Outer Temples of the Mountain Resort. “As the sun rose on the palaces of Chengde I experienced one of the most mind-expanding moments of my first stay living in China,” he reflects. “Chengde impressed me as no other place in China. . . . Manchurian palaces spread in the valley alongside the river surrounded by pine forests. . . . This palace complex was the ultimate statement of Zen and Taoist co-emergence of philosophy. But that is only where it began.” (48)

Laurence mentions the Putuo Zongcheng Temple and the Xumi Fushou Temple, which are imperial replicas of Tibet’s Potala Palace and Tashilhunpo Monastery respectively. These tantric influences that came to dominate the Qing spiritual consciousness were initially political calculations that morphed into sincerely held spiritual ideals over time. The Qing monarchs, in particular the Kangxi Emperor (1654–1722) and his grandson the Qianlong Emperor (1711–99), “. . . would summer in Chengde and spend their days hunting with leaders of the other ethnic groups, Mongolian, Tibetan, building camaraderie and most important consensus [my emphasis]. . . . Chengde as a palace complex served as a vast mandala. For the Qing emperors everything was there.” (49)

Kangxi and Qianlong understood that consensus is a fundamental part of governance. In many ways, reaching consensus (especially among such a diverse group as the Mongolians, Tibetans, Han, and Manchus) indicates consent for the emperor to command and execute his vision or plan. “Consensus” derives from the Latin root consentio: to feel together, to experience together. This is the beautiful secret of how the best emperors understood leadership: that they needed to express Buddhist interconnectedness through embodying the consensus of tianxia, of the empire, of their world.

The Buddha-dharma has enjoyed a nearly 2,000 years-long history in China (which is longer than that of Buddhism in any other region except perhaps of India and Sri Lanka). Yet it was only the Qing emperors that constructed their “interface,” the Chengde Mountain Resort, as a mandala. But the mandala is not sectarian: as Laurence notes, all of China’s “philosophical streams” could be found in the temples surrounding the Mountain Resort’s valley. (49) Buddhism, Daoism, and Confucianism are “streams” rather than religions, because they help humanity to understand and honor the subtle universal energies, the natural elements, and the cosmos.

Each temple in the Mountain Resort represents an aspect of Buddhist, or more broadly, spiritual truth that the Qing spread, through their mandalas and Vajrayana power, across China. Little wonder, then, that places like Puning Temple or Xumi Fushou Temple, despite their relatively recent history, are among the most important locations for Sino-Tibetan Buddhism today. The emperors’ voices can still be heard echoing the mantra of “Om mani padme hum” in our time. For this holy mantra was inscribed on the helmet of Qianlong’s ceremonial armour, to afford him sacred protection in martial battle.

Reference

Laurence Brahm. 2024. Gate of Nine Dragons: Searching for Kung Fu. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Open Page Publishing Company Ltd.

See more

Avalokiteshvara’s Thousand-Armed Reach in Puning Temple

The Sino-Tibetan Legacy of Unity at Xumi Fushou Temple, Chengde