“And what is that ancient path, the ancient road traveled by fully awakened Buddhas in the past? It is simply this noble eightfold path, that is: right view, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right immersion. This is that ancient path, the ancient road traveled by fully awakened Buddhas in the past.”’

Nagarasutta

Like many that grew up reading about myths and legends, Anglophone books about the civilizational legacy of “Western” myth encompassed quite a large and diverse region that, in an overwhelming majority of its cultural expressions and historical incarnations, would never have considered itself Western at all. Take, for example, the Mediterranean, North Africa, and the Middle East, where much of Western culture takes its inspiration and inheritance. Leaving aside the increasingly contested idea that the Greeks somehow saw themselves as a unified culture (let alone one that would be lumped in by future historians as part of the “Greco-Roman West”), they and the Hebrew people (or the Israelites) were in contact with a force profound and sophisticated enough to defy all categorization: Ancient Egypt. In many ways, the thought processes, spiritual visions, and value systems of the Ancient Egyptians was much closer to that of the Indians.

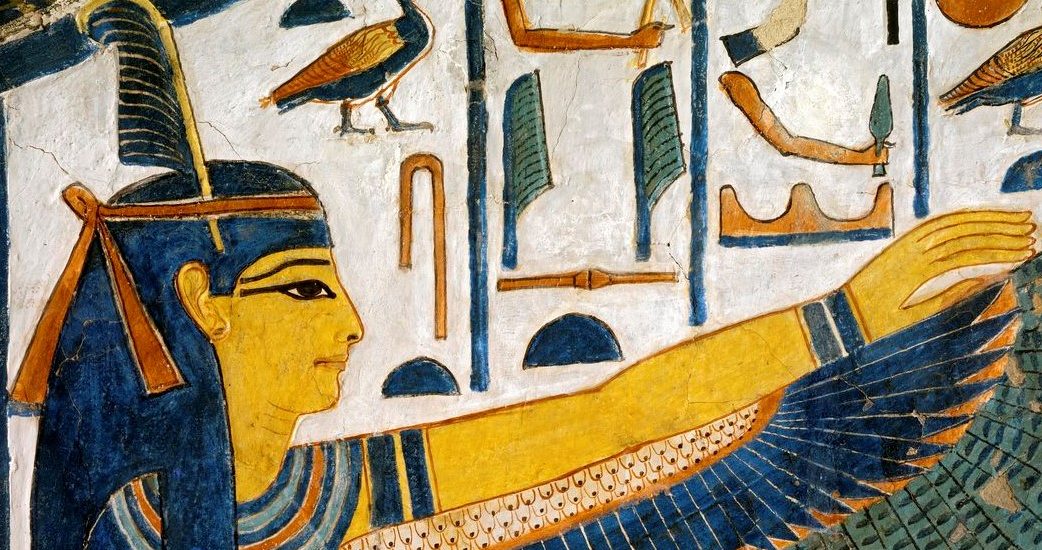

The cliché image that is commonly brought up when comparing Ancient Egypt and India is the lotus, which enjoys a sacred place in both Indian and Ancient Egyptian iconography. Yet their aesthetic and significance are somewhat different. The Egyptian lotus is scientifically known as nymphaea caerulea, while the Indian species is called nelumbo nucifera. The lotus in Egyptian mythology represents not just the creation of the world, from which Ra-Atum rose from the waters of nothingness, but rebirth from death to life. Meanwhile, in Buddhism, the lotus represents the transcendence of rebirth and conventional existence altogether, with Nirvana being quite different from life in the field of reeds overseen by Osiris, lord of the dead. Ma’at, at least in her anthropomorphic form as a winged woman, is said to have been born from Ra-Atum, whilst the Dharma is beginningless and endless, and Buddhas and bodhisattvas share its cosmic principles at a philosophical level (the Dharmakaya is what is common to all enlightened beings).

Still, I am struck time and again by how Ma’at, the Egyptian principle of cosmic order, represents the idea of cosmic harmony and, for the dead whose judgment is imminent, personal alignment with said harmony. It resembles an Egyptian expression of Dao or the Way – the path of Dharma, even.

I had thought about this only sporadically, sometimes over a period of several years. After all, Ma’at herself is somewhat forgettable. While Buddhism places the impersonal Dharma at the heart of the Three Jewels, Ma’at is overshadowed by more prominent deities in the Egyptian pantheon, from Horus to Isis. This is all the more curious given the importance of her role in the Weighing of the Heart of the Soul ceremony. Before the deceased enters the afterlife, their heart, which represents their soul, must be weighed by Anubis on the scales of justice against one of her feathers. Should Thoth record their heart as being heavier than Ma’at’s feather, Osiris will pass judgment and consign them to oblivion in the maw of the Devourer, depriving their sousl of the bliss of eternal life.

The deceased, in other words, must live in accordance to Ma’at, just as the path to happiness and eventual enlightenment is living according to the Dharma. Living true to Dharma consists of accepting the Four Noble Truths and applying the Noble Eightfold Path, while Ma’at means conformity with the gods’ will, living in a way that reflects the universal order found in the heavens, and cosmic balance. As far back as the Early Dynastic Period (3150–2686 BCE), priest-astronomers charted the empyrean and traced the movements of the stars, and the orbits of the planets. Modesty, reasonableness, cooperation, and looking toward the horizon of eternity was preached as the right way to confirm to the cosmic movements of the sun, moon, and stars. Therefore, “The Egyptians believed strongly that every individual was responsible for his or her own life and that life should be lived with other people and the earth in mind. In the same way that the gods cared for humanity, so should humans care for each other and the earth which they had been provided with.” (World History Encyclopedia)

Both Ma’at and the Dharma, in both their Buddhist and Hindu expressions, are the natural order.

While Buddhist conceptions of the Dharma are no longer based in astronomy, the Dharma is the universal truth, applicable to all and unrestricted by ethnic or tribal group, national loyalties, or cultural inclinations. Living according to higher principles with a view to religious practice is also a priority for Buddhists, with the Three Marks of Existence being perhaps the single most remarkable divergence from the Egyptian worldview.

What is clear is that Ancient Egyptian Ma’at, while restricted to Egypt historically, is much more universal and applicable than we realize. We can see reflections of its principles in certain aspects of the Buddhadharma, and through exploring the myths of old alongside the living teachings of Buddhism, we can drink from the well of wisdom of both . . . whether we are reborn in the field of reeds or the Pure Land.

See more

The City (Sutta Central)

Ma’at (World History Encyclopedia)

Related blog posts from BDG

Dharma and the All-Divine: New Age and Buddhist Thought with Rebecca Wong Howe