Statue of Kumarajiva outside the Kizil Caves. From China Discovery

There are two “buzzwords” in the Buddhist world today. One is obviously mindfulness and has dominated contemporary discourse for decades. The other is translation, and despite being overshadowed by mindfulness to some extent actually remains one of the most important activities of the global Buddhist community today. Not only are some of the most ambitious Buddhist-related initiatives related to translation projects, such as Khyentse Foundation’s 84000.

This is not surprising: translation, apart from being an art in and of itself, is the crucial vehicle for communicating the Buddhist teachings in a coherent manner. The stakes are especially high when it is not entirely certain when (or how many of) the Buddhist scriptures can be translated into a given language.

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche has always acknowledged the relevance of Chinese civilization in functioning as the repository of ancient Buddhist teachings, particularly in relation to its diffusion through East Asia in medieval times. “While a few great Indian emperors supported Buddhism in its early days, dozens of Chinese emperors supported Buddhism over the centuries,” he said. “And while Buddhism was long ago virtually eliminated from India, the Chinese fully adopted Buddhism as part of the Chinese civilization.” (Khyentse Foundation)

This month, Khyentse Foundation launched Kumarajiva Project, with the objective of translating “all of the texts in the Tibetan canon that are not available in the Chinese canon . . . the bulk of which are the shastras (the commentarial texts of the great Indian masters), from Tibetan into Chinese. Eventually, the project will also translate the texts from other Buddhist canons, such as Sanskrit and Pali, into Chinese.” (Khyentse Foundation) Whereas the works of 84000 are intended for a global, English-reading readership, this epic new project—projected to take an entire six decades—is aimed at readers of Chinese.

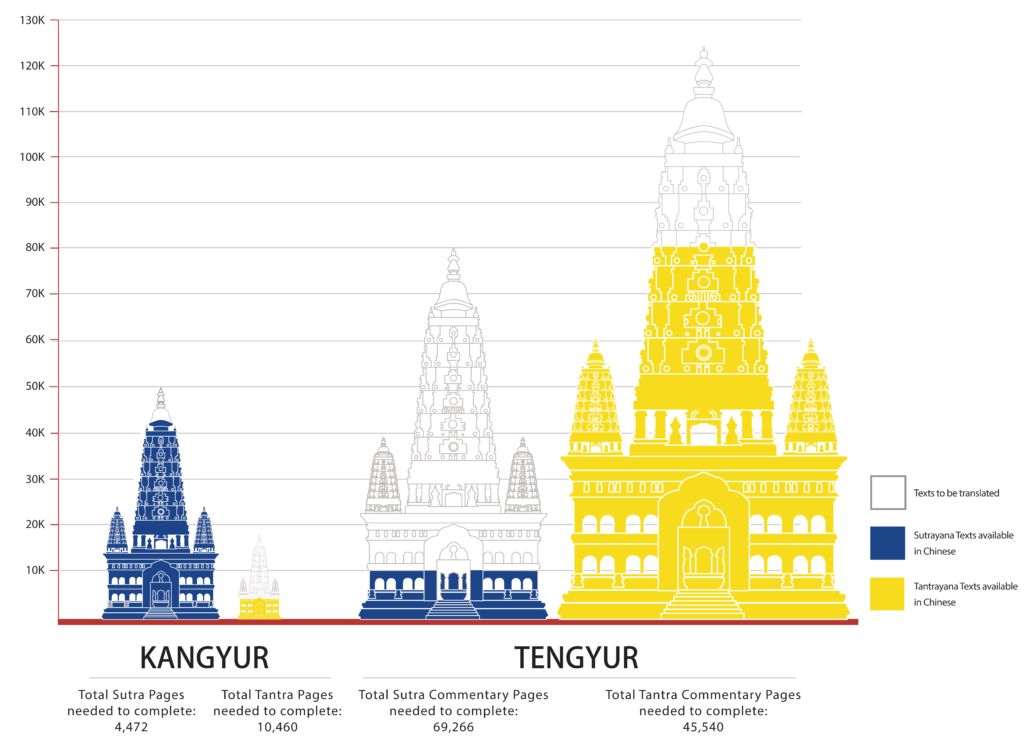

Buddhistdoor Global reported on this initiative in April, and the full scale of the project demands an all-hands-on-deck approach: “The Tibetan Kangyur, the written words of the Buddha, contains an estimated 70,000 pages of text, 15,622 of which have not yet been translated into Chinese. The Tengyur, the commentaries to the sutras and tantras in the Kangyur, contains an estimated 161,800 pages, 119,042 of which have not yet been translated into Chinese.” (Khyentse Foundation)

The name of Kumarajiva is a fitting tribute to this most eminent of Central Asian translators. The historical Kumarajiva (344–413) translated not only seminal sutras into Chinese, among them the Perfection of Wisdom Sutra in 8,000 Lines, Vimalakirti Sutra, Diamond Sutra, Lotus Sutra, and Amitabha Sutra, but also various Mahayana commentaries and manuals. His translation style was groundbreaking, departing from previous generations of Central Asian or Indian translators by abandoning “concept-matching” with Daoist or local folkloric terms. He balanced this concern for accuracy with a preference for polish, preferring to communicate the meaning of the text rather than insisting on word-for-word equivalents.

While 84000 starts from a more “tabula rasa” base—there is no such thing as a Western or canon, despite the surge of European-language translations in the 19th century—the Chinese tradition already has more than a millennium of experience translating and codifying texts from Sanskrit and other Indic scripts into Chinese. Khyentse Foundation itself acknowledges: “Buddhism is already deeply rooted in Chinese culture with an established, revered canon, which many consider complete and perfect as it is. Further, the Chinese canon, having been compiled over 19 centuries, has its own languages, styles, and characteristics. To add to the Chinese collection of Buddha’s teachings in a way that both respects the texts of the Chinese canon and also makes the newly translated texts accessible to modern Buddhist readers requires skill and sensitivity.”

There are already 19 works translated as part of a pilot launched in 2017. Now Kumarajiva throws open its doors to interested translators and scholars, approaching this monumental, long-term task with the Daoist attitude of “dripping water penetrating stone.” Kumarajiva himself would be proud.

See more

The Kumarajiva Project is Launched (Khyentse Foundation)

How India Is Squandering Its Top Export: The Buddha (HuffPost)

The Kumarajiva Project and 84000: What’s the Difference?(Khyentse Foundation)

Related news from Buddhistdoor Global

Khyentse Foundation Plans Ambitious Undertaking to Translate Tibetan Buddhist Canon into Chinese

Related features from Buddhistdoor Global