Last time we picked off from our exploration of Japanese Buddhist sculpting (butsuzo), we had seen how the Genpei War of 1180–1185 saw the Minamoto clan establish the Kamakura Shogunate, marking the close of Heian period and a protracted period of relative decline for Japan’s ancient aristocracy. This meant that the blue-blooded Fujiwaras’ studios of choice found noble patronage to be political millstones, while the working-class realism of the Kei school (or Keiha) became lionized by the hardy, fierce daimyo warrior class.

As David Bilbrey notes on Yujiro Seki’s Butsuzōtion blog, the war had left two critical centers of Buddhist influence, Kofuku-ji and Todai-ji, in ruins. The Keiha busshi rose to prominence during this period, with individual sculptors ascending to heights of fame not reached since Jocho. Unkei, who was the son of Keiha head Kokei, is one such figure. Kokei had spent about a year growing roots in Nara and soliciting shogunate patronage after the Genpei War. We do not know the exact reasons why (perhaps to gain further favor or, alternatively, the shogun had already invited Kokei or asked him to send a representative), but Unkei left Nara for eastern Japan, establishing sculpture communities rapidly at Izunokuni in 1186 and Kanagawa in 1189. These groups were the Ganjojuin and Jorakiuji respectively, and they focused on sculpting Buddhist deities and figures that were familiar to the masses and high in popularity. Aesthetically, the militaristic Minamoto family enjoyed the mighty divinities of Bishamonten and Fudo Myo-ō, who they believed had won them the war.

Traditionally, these two were not prestigious subjects: in fact, they flank core Buddhas like Amida as guardians. Bishamonten is attested all the way back to the Pali Canon as a celestial deva called Vessavaṇa. Somehow, a separate Indic deity known as Vaiśravaṇa (Kubera in Hinduism) became conflated with the Pali personage and the result was the figure of Bishamonten. He is an armor-clad god of war, patron of warriors, and a punisher of evildoers. Meanwhile, Fudo Myo-ō is the Japanese expression of Acala, who originated as a tantric deity in India and rose to prominence in the 8th to 9th centuries, before being carried over to Tang China by Vajrabodhi and his student Amoghavajra (and subsequently to Japan).

Unkei stayed in the east of the country for about a decade and returned to Nara in 1196, taking with him the preferences and directives of the shogunate and its allies. The Kei school subsequently saw a rivalry between Unkei, the eldest son of Kokei, and Kaikei, Kokei’s star pupil. Both saw themselves as heirs to the school’s leadership. However, it is said that their rivalry was a reasonably healthy one, which refined the school’s mastery of wood sculpting and pushed the busshi to excel in their craft. Much of their time was spent repairing statues from the Heian era.

Soon, the great commission at the great Todai-ji began in 1203. Bilbrey calls this “the most jaw-dropping showdown in woodcarving history.” (Butsuzōtion) A monk called Chogen fundraised much of the rebuilding and statuary at the temple. The specific commission was for the production of a pair of Kongorikishi guardians (or nio, protective manifestations of the warrior bodhisattva Vajrapani) at the Great South Gate of Todai-ji. This was the project of a lifetime for the Kei school. Bilbrey notes that there are relatively few examples of the nio after the end of the Asuka era in 710. Unkei and Kaikei both knew that, depending on the results, their school would either be immeasurably elevated in prestige and power, or suffer irreversible disgrace and loss of face.

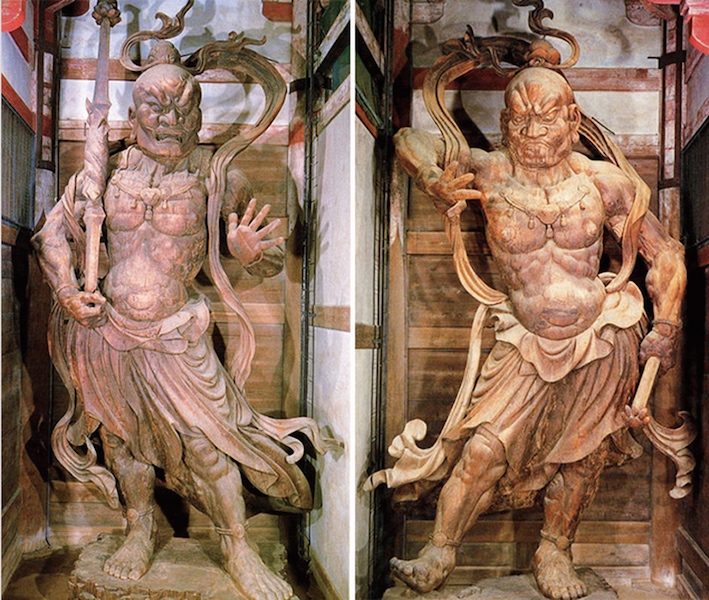

Kaikei’s personal style, Annami, was a carving technique that emphasized gentler strength and producing contours inspired by statuary from the Song Dynasty in China. Fortunately, the two rivals came together, determined to give the shogunate a masterpiece for the ages. For now, Kaikei would defer to what Unkei saw as the Minamoto clan’s preference: to make the guardian figures as large as possible, with masculine, virile muscles that rippled with energy, saturating the very gates of the temple with protective reassurance for devotees and menacing dread against all interlopers and enemies of the Dharma. They are characterized as boisterous, wrestlers, dancers. And the result after 69, 70, or 71 days (the exact number is debated) was a literally gargantuan achievement by only 20 Keiha sculptors: from the base up, two 28’ tall Kongorikishi statues that you can still visit today, to see them watching over the Great South Gate.

That the Kei school was able to complete these statues so meticulously, so perfectly, and so speedily, means that they had been prepping themselves for probably the entire decade that Unkei was out of Nara. Bilbrey suggests that they might have been constructing, as models for the final commission, scaled-down partial wooden models. The scale of this architectural ambition for assembling woodblock is described as yosegi zukuri, but the sheer scale of the woodcarving seems to warrant a separate category: daiyosegi zukuri. As Bilbrey describes:

The central core of each statue is comprised of several large-scale vertical beams of timber, joined with oversized metal staples. Various tenon joins affix shapes and other surface details which protrude over their respective centers of gravity. Arms, abdomens, draperies, facial details and other iconographic details for these statues all needed to be attached, resulting in upwards to 3,000 pieces of wood for each statue. Yosegi zukuri historically implies completely hollowing out the statue from the inside, but such a technique would have forced figures of such scale to collapse from their own weight. An early 1990s conservation effort of these figures revealed that though there were hollow pockets peppered throughout the statues, the majority of what was on the inside was solid wood. Originally built without guy wires to stabilize their upright positioning, these figures were the largest freestanding wooden sculptures in the ancient world. In terms of a showdown during this, the Renaissance of carving Japanese Buddhist sculpture, we are the fortunate ones, for this “contest” could easily be determined a draw, with each powerful figure complimenting the other, as masterworks of Kongorikishi should.

(Butsuzōtion)

Upon the completion of this duo of utter masterpieces, the bakufu honored Unkei with the title of Hoin, the highest rank for a master of Buddhist sculpture. His journey was far from over, however, as his realism still had some time to mature, before he accomplished this with a commission at Kofuku-ji. He was one of Japan’s most acclaimed sculptors, if not its most well-known, and the unmatched standards that he set for Buddhist sculptors would reverberate throughout Japanese history.

Carving the Divine is now crowdfunding for distribution on IndieGoGo

See more

Nio @Renaissance (Butsuzōtion)

Related blog posts from BDG

Of Artisans and Aristos: Butsuzo Flourishing in Japan

Jocho: The maestro that started Japanese Buddhist Sculpture

The Yuji Experience: A Singular Voice for Japanese Buddhist Sculpture