Cast yourself to the year of 1057. Jocho has died, and in just a couple of centuries, medieval Japan’s imperial court and nobility would give way to a new order of military leaders in the form of the shogunate. Jocho was the first true native Japanese pioneer of Japanese woodcarving (butsuzo), the discipline’s prime practitioner (busshi). So influential was Jocho that he left behind three schools of butsuzo: Enpa and Inpa, which were based in the imperial capital of Kyoto, and the Kei studio, which was located in nearby Nara. The En and In schools were founded by Chosei and Injo respectively, and early on (thanks to the great prestige of Jocho) were creating Buddhist sculptures for the imperial court, which itself prided the adoption of Buddhism as a sign of spiritual refinement and aesthetic taste, as well as cosmopolitanism and prestige attached to association with Chinese culture.

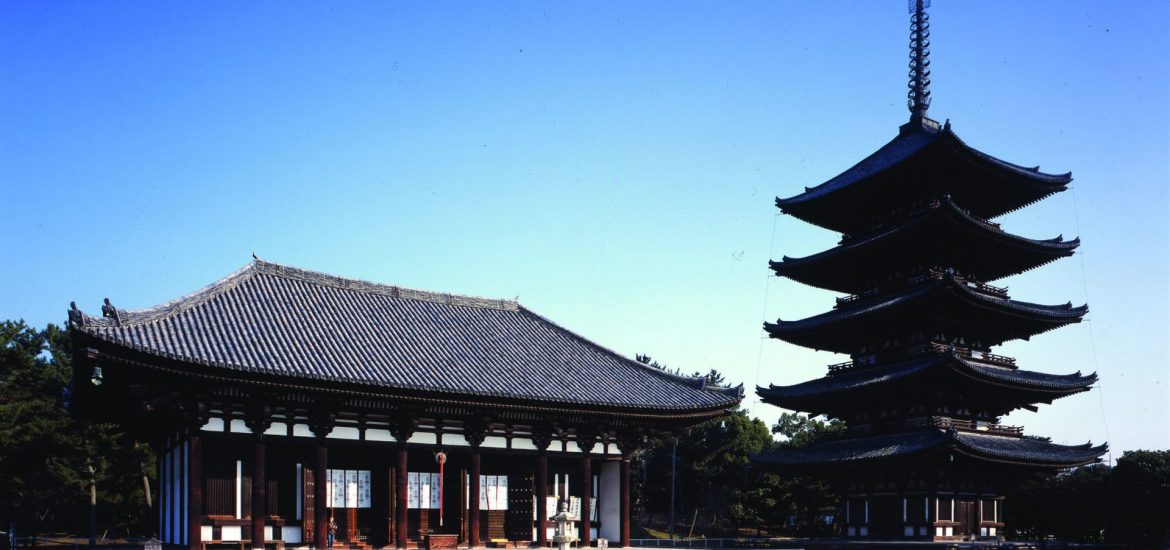

Where the Japanese aristocratic clans were, the Fujiwaras were inevitably present. According to most mainstream historians, the Fujiwara clan influenced or directly steered a great portion of the imperial court’s fate, intermarrying their women with the emperors, crown princes, and other dynastic figures, while the men acted as regents, high ministers, and politically connected retainers. The founder of the clan, Fujiwara-no-Kamatari (614–69), was famously Shinto, and did his worst to halt the creeping influence of Buddhism at the court. But his wife, Kagami-no-Ōkimi (d. 683), had a great temple in Nara constructed when he fell ill. Kōfuku-ji would henceforth become the tutelary temple of the Fujiwara clan, serving as its connection to the Buddhist monastic powers and exerting even more influence over the imperial court.

Noble House Fujiwara predictably, took an interest in Buddhist art. By the time of Jocho’s death in the 9th century, its tastes in butsuzo was dominant, at least at the outset. As David Bilbrey writes for Yujiro Seki’s Carving the Divine blog, Butsuzōtion:

“The Fujiwaras’ refined tastes were reflected in Inpa and Enpa Butsuzō aesthetics, which took Jōchō’s canon and steered it to further cater to the softer, more elegant direction preferred by the wealthy imperial courts. Buddhist statuary of the region was dominated by these wildly successful Kyoto schools, while the Nara-based sculptors took a relative back seat due to having no ties to the Fujiwara government.”

Butsuzōtion

This changed with the brutal Genpei War (1180–85), when the Minamoto clan crushed their Taira rivals and established the Kamakura Shogunate. This marked the end of the Heian period, the era dominated by the Fujiwaras and other noble clans. The rise of the daimyo warrior class, and the now-established importance of military leaders that could mobilize large armies of samurai to protect or coerce, relegated the emperor to puppet rule, therefore rendering court politics a bit of an insular joke compared to the deadly serious business it once was. With the shift of power to the power base of Kamakura and the shogunate, the Kei studio’s lack of support from the Fujiwaras ironically became a strength. Buddhist art by the Kei busshi had something of a working-class realism about it, and its intense strength of body language and forceful expressions were popular among commoners compared to the soft, sumptuous aesthetics favored by the imperial court.

The end of Fujiwara political dominance at the end of the 11th century coincided with the decline of the En and In schools they had supported. The Kei school was from here on the dominant studio. For a while, there was competition as well as collaboration, and Bilbrey notes that the three schools came together to refurnish almost 900 life-sized wooden sculptures for Sanjūsangendō in Kyoto sometime before 1265. Indeed, Jocho’s Wayo style would never fall out of fashion, but the elitist In and En schools were out. Buddhist art, from hereon, would be more grounded and less intangible.

Do not feel sorry for Noble House Fujiwara, however: relative to the 99.9 per cent of common Japanese people, and even to their own aristocratic rivals, the Fujiwara lineage thrived through its five regent houses. The bakufu, from Oda to Tokugawa, sought their loyalties and women all the way up to the Meiji Restoration (1868–99). Then the Meiji Oligarchy merged the kuge houses of old school nobility with the deposed daimyo to form the kazoku, “exalted class.” For a few decades, they served in the Imperial Diet’s upper house, the Japanese equivalent of the House of Lords. These privileges ended with the Second World War, and with them the last trace of political influence of the Fujiwaras. Still, two prime ministers on the modern period, Fumimaro Konoe and Morihiro Hosokawa, claim descent from them, and Fujiwara blood runs strong in the imperial family due to centuries of intermarriage. And the art they once patronized continues on to this day.

Carving the Divine is now crowdfunding for distribution on IndieGoGo

See more

Japan’s Old School Rivalries (Butsuzōtion)

Related blog posts from BDG

Jocho: The maestro that started Japanese Buddhist Sculpture

The Yuji Experience: A Singular Voice for Japanese Buddhist Sculpture