What is a god?

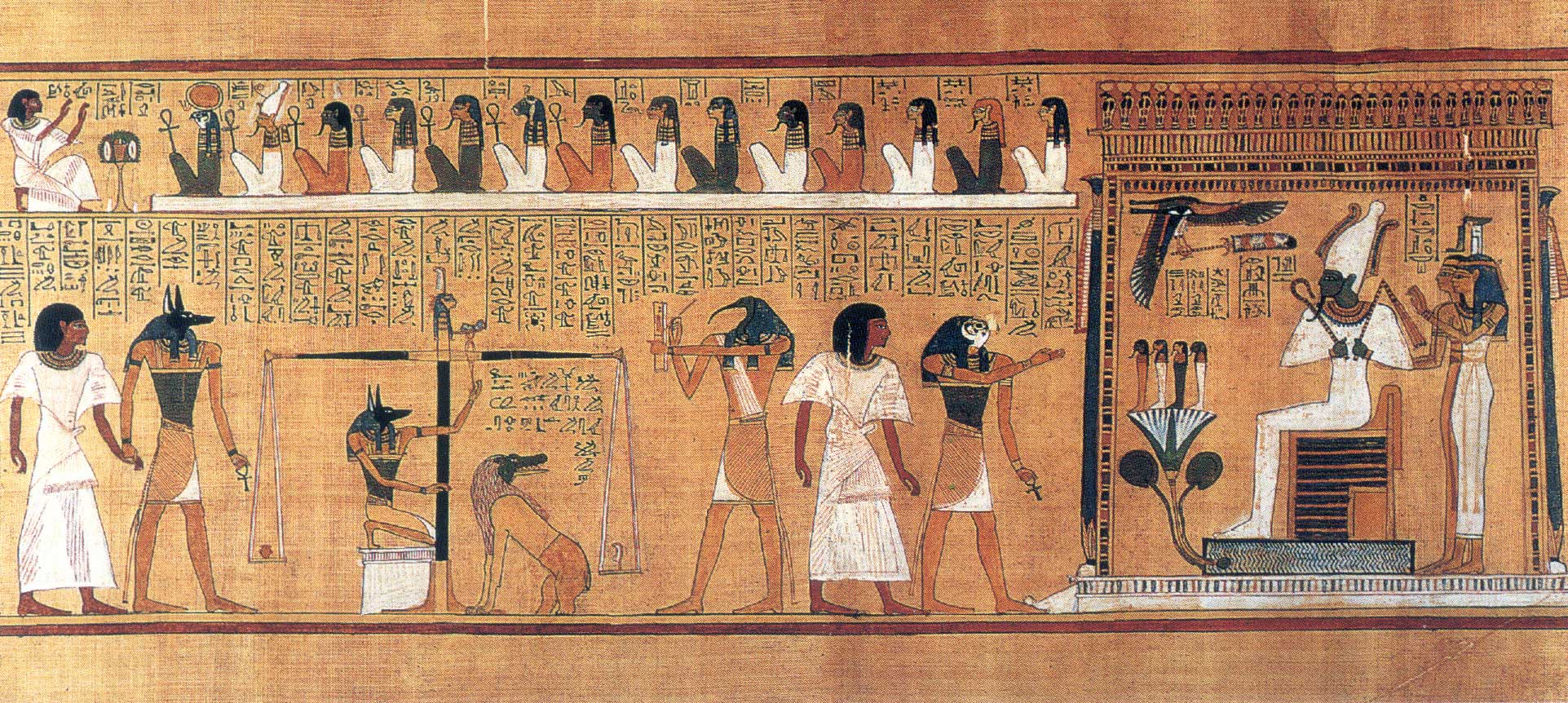

Human figures with the heads of animals are intentionally absurd images. They look frightening, ridiculous, inexplicably endearing. They arrest us, shake us out of our dull, seen-it-all before everyday complacency and force us to take a second look at them because they reveal themselves as intentionally strange beings. In ancient Egypt, people envisaged their divinities metaphorically, as beings representing worlds beyond the boundaries of human knowledge.

The god of the sun “is like” a falcon that soars across the sky, and a deity that is fertile and virile has the head of a cow or bull. The gods use a visual language to show us that their abilities go beyond the five senses and our normal perceptions, that they have powers that we see as part of the cosmos and the natural world.

Yet despite their weirdness—for gods are in the most pure sense weird to human beings who can’t understand them fully—the Egyptians understood that they relate to the experiences and lives that we know. Gods are presences that embody cosmic energies, including the forces that human beings feel viscerally. Love, hatred, desire: they embody the plasma that formed the oldest stars and galaxies of the cosmos, the fabric of time, and the matter of our universe.

Yet despite their weirdness—for gods are in the most pure sense weird to human beings who can’t understand them fully—the Egyptians understood that they relate to the experiences and lives that we know. Gods are presences that embody cosmic energies, including the forces that human beings feel viscerally. Love, hatred, desire: they embody the plasma that formed the oldest stars and galaxies of the cosmos, the fabric of time, and the matter of our universe.

Since gods are forces of creation, they also dwell within it and in the sentient creatures that are made of stardust and collapsed universes. Prime celestials of love, anger, war, the hunger for knowledge—throughout history, cultures have identified human yearnings and elemental, primal needs and phenomena that still cannot simply be explained by data or logic.

In Asia, the popular motif of Avalokiteshvara with a thousand arms does not indicate that the bodhisattva literally has no more and no less than a thousand arms, no more than the “western” paradise of Amitabha Buddha is in the direction of my left hand. I believe that the pantheon of the Mahayana tradition is realer than our world of samsara, but our words and experiences are only broken vessels to capture a gushing tide, buckets scooping water out of a flowing river.

“For the curse of life is the curse of want,” said Lacan. Want, life, and the universe are tied up in our experiences of divinities, and only our attainment of insight—through the Buddhas, the embodiments of Dharma, of what is—can bring us beyond life and death, and even the gods themselves.