Every artist works with archetypes and plays with symbolism, weaving unique imagery into their canvas that brings to life their journey and work. For an artist immersed in spirituality and mysticism like Rebecca Wong, painting visual reminders of cosmic realities and mystic planes are second nature. You might remember her as a tarot teacher and incense instructor straddling the worlds of Western mysticism and Vajrayana Buddhism. That was my profile of her spirituality. In this exploration of her beautiful art, we will see how her impeccable taste in painting and her unique themes are markedly more Asian in orientation, largely due to her artistic lineage, which is rooted deeply in China’s heritage and history.

Rebecca’s journey as an artist, art creator, or mystic of art began early in life, when she discovered that her family’s story involved a world of vibrant and dramatic colors, marked by creativity, romance, and heartache. “My grandfather had a mistress, May Chan, who eloped to Paris with none other than the Sino-French master of painting, Zao Wou-ki (1921–2013). I remember my father bringing Zao’s work back home to Hong Kong – I think I was around five or six – and I was struck with admiration by his chiaroscuro.”

In Paris, Zao Wou-ki had been painting with oil and was the first to integrate it with Chinese techniques. “I developed a consciousness, or awareness, of myself as having come from a family whose fate was intertwined with art,” recalled Rebecca.

At 14, while studying in Australia, Rebecca discovered a talent for painting, where she learned Western impressionism (she had a particular fondness for Monet). Years later, while studying an unrelated subject in London, she came across SOAS (which happens to be my alma mater). There, she stumbled on a pamphlet for guqin lessons with Li Xiangting, who was in turn taught Imperial Style calligraphy by Pujie, the brother of Puyi (the last emperor of China). Li Xiangting claims descent from the Qing emperors, and his mentorship of Rebecca kicked off her own artistic lineage with China’s last dynasty.

“As Teacher Li would say, to learn music, one should learn art. The spaces between notes and the ‘emptiness’ that provides the foundation for sound can only be understood through mastering actual visual space by painting forms onto the formless,” said Rebecca. Much more recently, she has encountered another mentor also surnamed Li, this time of the Dunhuang School of Art, from whom she has been discovering the meaning of painting.

Moisture. Wetness. Purity and cleansing. Water is a big part of Rebecca’s life, from the seaside to her love of Mediterranean aesthetics. It is also among the many meanings of “qing,” the character, that the Manchu dynasty’s de facto founder, Hong Taiji (1636–43), used to symbolize the “extinguishing” of the previous dynasty, the bright and burning Ming. No wonder, then, that she felt such a powerful connection with Yuanmingyuan (or the Old Summer Palace), the exquisite retreat and complex of manors and villas that the Qing imperial family enjoyed until its destruction in 1860. “The Qing emperors adopted Tibetan Buddhism and saw themselves as not only Vajrayana practitioners, but also emanations of Manjushri Bodhisattva,” she said.

“When I first began exhibiting my art seriously a few years ago, my very first series of paintings in October 2021 was based on Yuanmingyuan’s complexes. Of all the Qing monarchs, I admire the Yongzheng Emperor the most. He drastically expanded the original Yuanmingyuan and it has served as endless artistic inspiration for years.” Since Rebecca’s first exhibit, she has displayed other series of paintings, one in June and another two in October of 2022. I am so proud to have seen these exhibits and soaked in the special presence of the paintings in person.

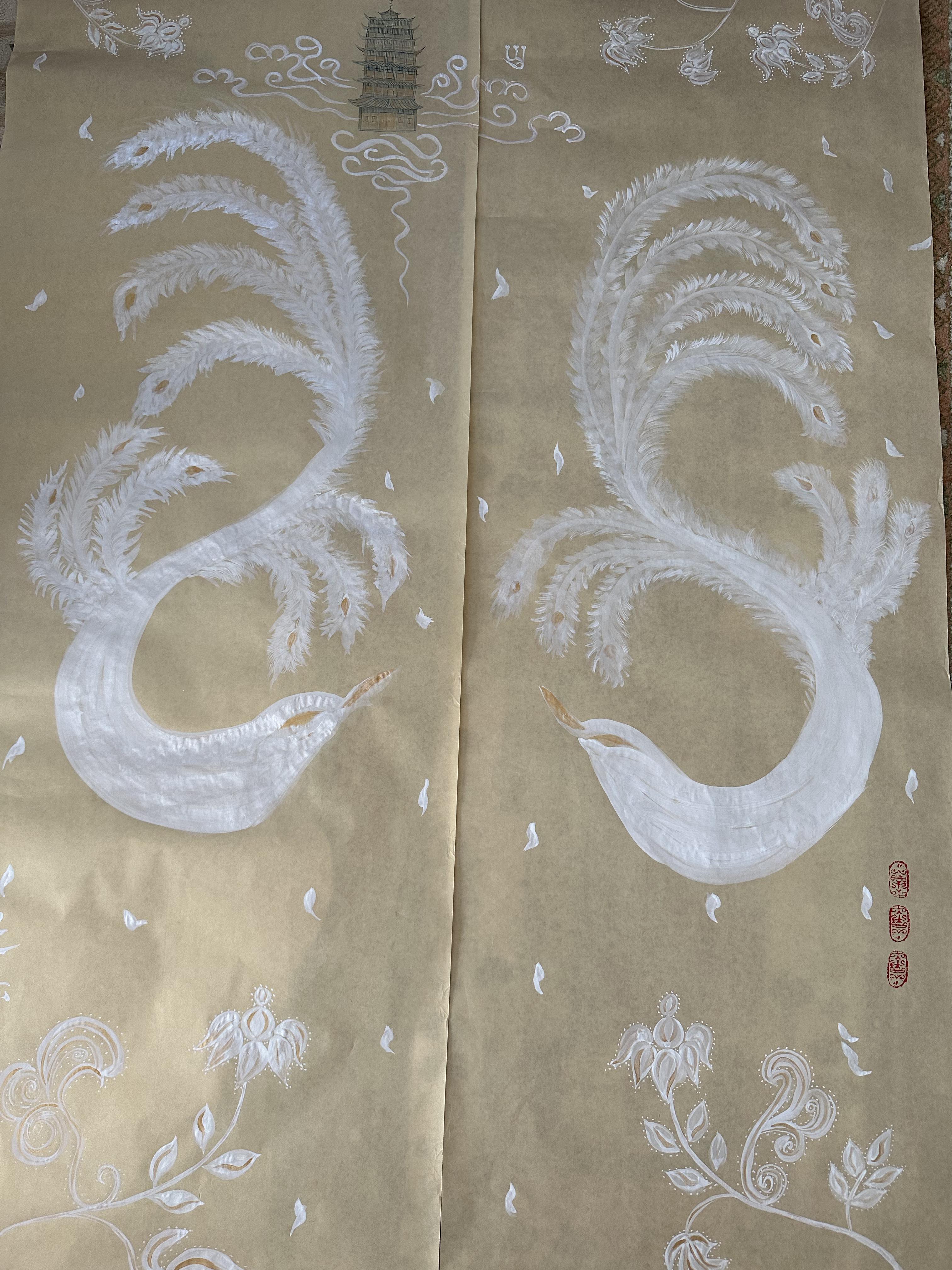

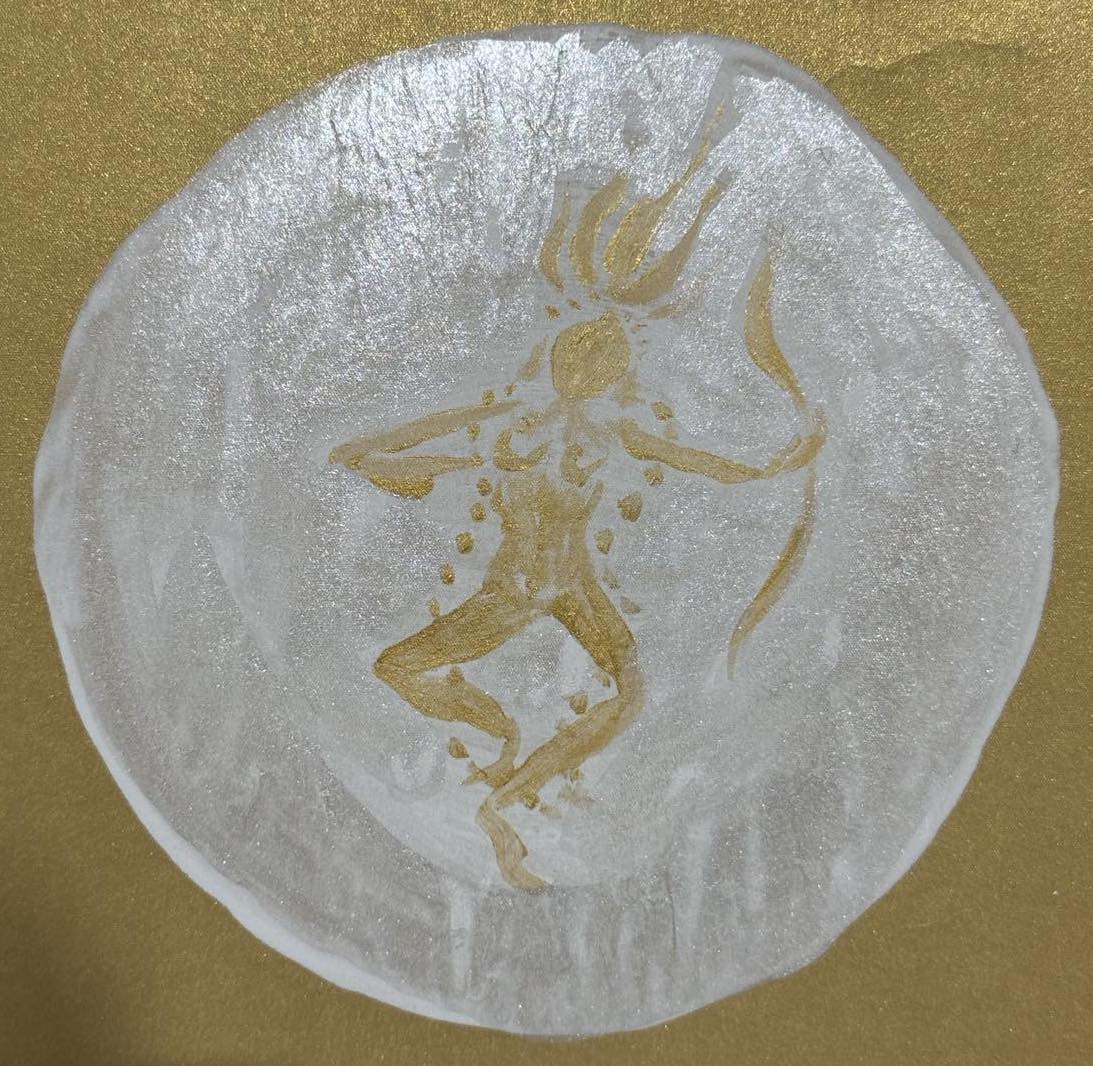

Her art features several common themes: floral rain, tantric deities, Sanskrit seed syllables, twin moons, and the lotus. Not only are they visually stunning, they also take the viewer into the world of archetypes. Rebecca resonates with specific tantric deities, such as White Tara and Green Tara, Cakrasamvara, and Kalachakra. One she has been drawing frequently is Kurukullā, a female, semi-wrathful yidam associated with rites of magnetization or enchantment. Thanks to Rebecca, Kurukullā’s cosmic dancing and healing presence has been increasingly powerful in my own life as well.

“The deities and the other archetypes bring meaning to my art. My paintings also feature pairings as themes. Moon disks are combined, my deities are in the yab-yum position of sexual union, and I often paint a pair of white phoenixes. All these symbolize duality, transmigration, and ascension. What else does my painting mean? For me, it means meditation. When I begin painting, I enter into a trance, and to facilitate this different space, I will light candles and incense.” This allows her to enter into visualization and create her art with pure concentration and inspiration.

“My artistic creations are my way of contributing to Buddhist flourishing,” said Rebecca. “I am not a meditator or a scholar, but I am a mystic and creator. I dance, I paint, and I teach incense seals. These are three of the 84,000 Dharma doors that I have opened for others.” She also is keeping busy with planning the founding of a new charity. “I have always preferred supporting women that want to study Buddhist wisdom. Currently, I seem most closely aligned with the Samtenling tradition of teachers, in particular the lineage of the late Thrangu Rinpoche.” Rebecca also has karmic affinity with Monla Khedrup Rinpoche, Kalu Rinpoche, and other teachers that are involved in the tradition of Dakini.

Recently, we have been sharing notes and conversations about Chöying Khandro’s new book, Dakini Journey in the Contemporary World (2023). Rebecca is growing increasingly immersed in the life of the sky-dancer, the fierce and sensual Goddess or ground of liberation. It would seem that she is growing ever more comfortable in her Buddhist identity, but this identity is only one of many in her kaleidoscope of a rich life. In the great Buddhist lesson of no-self, Dakini is a paradox. In embracing Dakini, Rebecca encounters the possibilities of all kinds of selves, and finally, as Chöying Khandro would say, her true self.