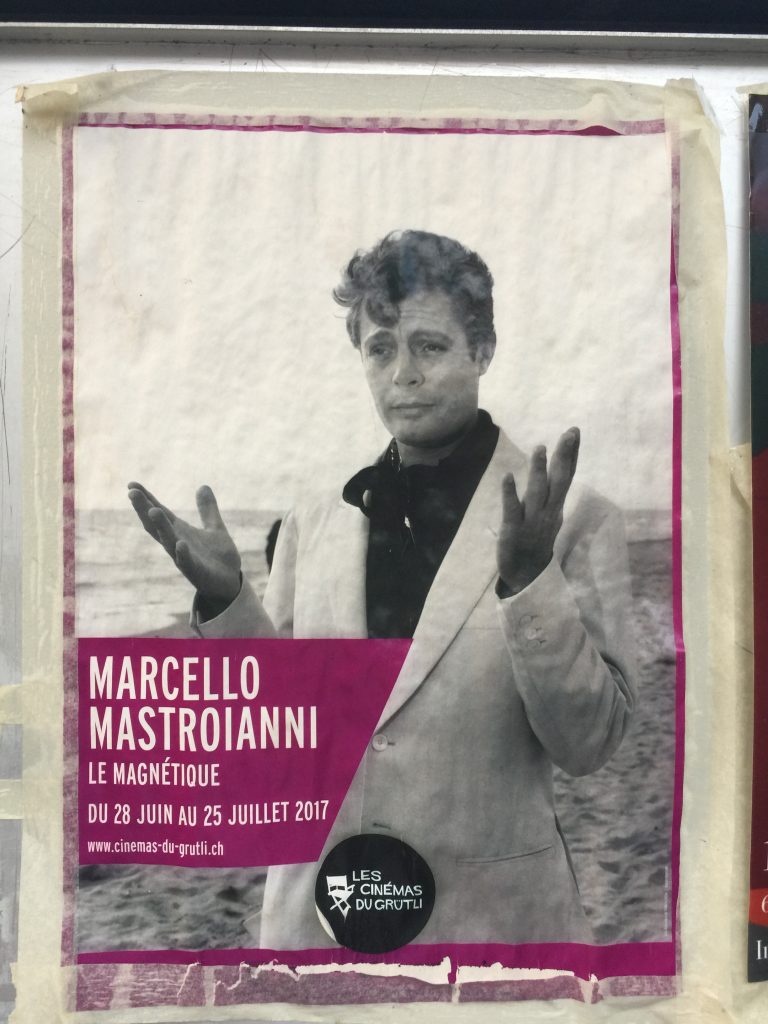

It’s a classic moment in film, one of quite a few from Federico Fellini’s black and white cinematic masterpiece. The charismatic but emotionally lost gossip columnist Marcello Rubini, played by Marcello Mastroianni, is at the beach, holding his hands up in bemused resignation as he struggles and fails to discern the shouts of a young girl in the distance. Eventually, he can’t make out her words and leaves. The girl’s name, played by Valeria Ciangottini (she was personally chosen by the director) is Paola and Marcello (Rubini) has seen the character before in a restaurant – a sweet angel from a lost world of innocent affection, when love just meant love and nothing else. What might have happened had he been able to respond to her waving and shouting? The implication is that it would have been an encounter far removed from and superior to his Roman world of fallen aristocrats, broken celebrities, and suicidal intellectuals.

But the causes and conditions just weren’t there. He certainly behaves that way. He doesn’t rush to her. He seems hardly desperate to escape the emptiness of his life and reach for that remote if possible alternative future. His languid posture as he kneels on the sand, his reluctance and even laziness to move at all, speaks of a spiritual lethargy and “giving up” that has crippled him permanently as far as Fellini is concerned. This is no Hollywood where the protagonist cornily realizes the error of his ways and makes amends.

Indeed, Marcello does not even find the strength and resolve to haul himself up from the seashore and run over to Paola. The distance between them does not even look that wide to me despite the camera’s hint that it is an unbridgeable gap, and any indication that he was going to find a way over to her would have, in an alternate universe, prompted Paola to wait for him or meet him halfway.

Observe his final shrug. Paola clasps her hands together, as if begging him to snap out of something. She is waiting for him to do so. He throws his hands up, dismissive of himself but also of her efforts. His farewell wave covers his darkening face, as if to hide his shame as he retreats. He turns away into the arms of another woman he shall surely forget the morning after, even though Paola watches his retreating form with a smile and gaze that I can’t describe as anything less than loving, adoring, and compassionate. That lasting shot of Paola’s face is truly haunting if one has felt invested in Marcello’s melancholy journey.

Marcello’s inability to hear Paola, the fact that her frantic gestures seem nonsensical to him, are all hints that he has lost the capability to chase after a better kind of happiness for himself and others. The right time has simply passed for him. It is a perfect example of unripened karma, of a tantalizing future that is physically right in front of Marcello – not in the romantic sense of course, but Paola certainly represents a possibility of being that Marcello perhaps could have related to, and even shared with her as a jaded but healing friend or father figure. But again, the film’s progression and Marcello’s actions reveal that the conditions are absent for this to happen.

La Dolce Vita is such a multilayered and multitextual film that I’m fairly confident a deeper, more analytical reading could uncover many Buddhist meanings and insights in multiple scenes. For now, I’ve concentrated on the final scene between Marcello and Paola because I think it is actually sadder than others that have traditionally taken the critics’ cake, such as the suicide of Marcello’s friend Steiner. It hints at the life that could have been had the conditions been set up differently, but without those conditions Marcello returns to a far more “samsaric” life, as purposeless as we found him at the start of the movie. His and Paola’s karmic fruit just aren’t in season.

Much has been written about La Dolce Vita’s structure and symbolism, such as the number of acts that seem to symbolize contrasting Christian virtues and vices as well as the interpretation of his exposure to different professions (writing novels, journalism, and hardnosed PR) as a descent from heaven to hell. Personally, I see the ending more as a poignant statement on paths crossing at the wrong time, conditions that aren’t met, and therefore happier endings that can’t be realized.