In The History Boys’ film adaptation (2006), schoolboy Dakin asks classmate Scripps: “Lecher though one is – or aspires to be – it occurs to me that the lot of woman cannot be easy, who must suffer such inexpert male fumblings, virtually on a daily basis. Are we scarred for life, do you think?”

Ever the sardonic observer, Scripps (who happens to be one of my favorite fictional characters) replies wryly, “One should hope so.”

To me, as a former boarder of an all-boys’ school where masculinity was constantly being negotiated and challenged, there are three things notable about this brief exchange. One, is that masculinity is whatever we want it to be: see how Dakin casually equates being a man with being a pervert or hungry sexual being, even if it is amateurish and embarrassing to everyone involved. Attaining it also has nothing to do with actually being happy or finding peace: note how Scripps says one should hope to be scarred, if one has done all the right things. And finally, Dakin observes that the acquisition of masculinity, or being seen as “a man,” can indeed come at a cost, specifically to “the lot of woman.”

One of the most insightful books about gender relations, patriarchy, and feminism I have recently read is Ivan Jablonka’s A History of Masculinity: From Patriarchy to Gender Justice (2023). Even though patriarchy is universal across all society, Jablonka’s genealogy of gender relations is a hopeful one (patriarchy is not biologically destined). I find what he says about our world shaped by said patriarchy fascinating, especially when it comes to masculinity:

. . . a man must constantly prove that he is one. Masculinity carries within itself a fear, that of being unworthy of the male sex. It is therefore intrinsically fragile, self-doubting, afraid of not meeting the standard: hence all the provocations, ostentatious behaviours, sacrifices, all the ‘fine deaths’, which only raise the stakes even more.

The crises of masculinity have existed since antiquity, and independently from any demands made by women.

(Jablonka 2023, 178)

If even kings, CEOs, and champions must constantly be proving their masculinity, what happens when an inadequate boy or man fails any one of these tests? What happens if they just fold and fall apart?

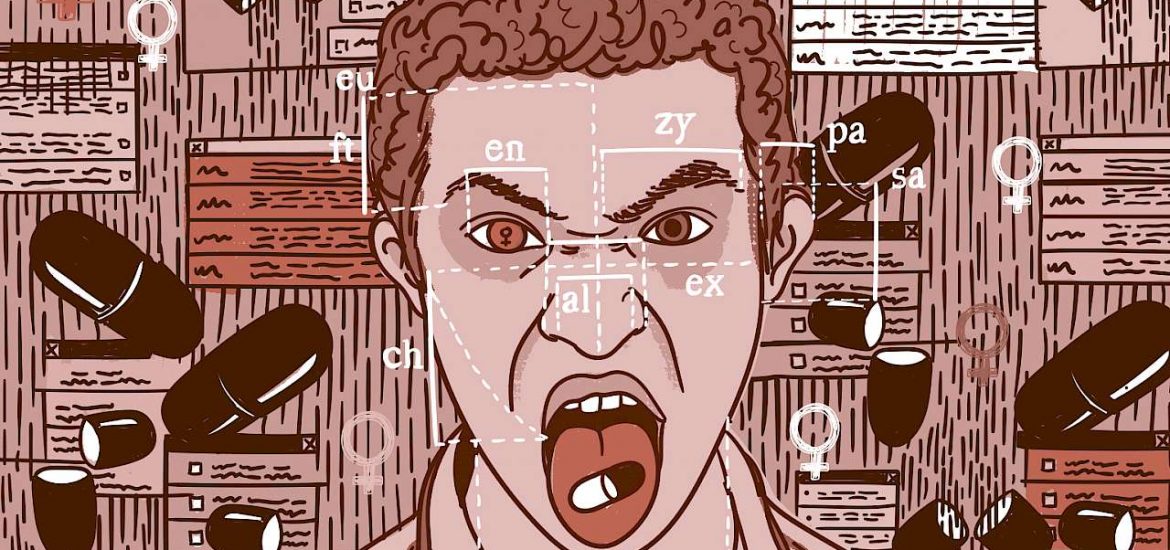

The schoolboy world of The History Boys has, in some ways, remained constant – “earning” masculinity, holding on to it, and even understanding what it is, is still a big question mark. Yet it has also changed dramatically and forever due to young people’s immersion in social media and the Internet world. Here, new discourse and terms – specifically, “incels” and “the black pill” – have arisen to express the hurt, loneliness, and alienation boys and young men feel when they fail to live up to society’s “trials” of masculinity: getting a girlfriend, accruing wealth, work experience, and social capital, and so on. Many of them turn to bitterness and the “black pill” when their rites of passage are disrupted or “never even began,” as they like to say. Most are full of rage against broad groups like women. Needless to say, such blanket dislike and disdain only serves to isolate them further, since people connect best on an individual-to-individual basis.

Most assessments of black pill ideology classify it as an ideology of biological determinism, fatalism, and defeatism. I think it is broader than not being able to find a mate, have sex, or get married. It is rage and despair at not being able to fulfil the “masculine.” It is a subculture of neuroses about “inadequate masculinity” that now have an endless online space to proliferate.

While what black pillers often say is extremely unpleasant, the danger of the black pill ideology does not necessarily come from one of its stated premises: attractive people have it easier. Furthermore, socially constructed standards of beauty (ideas about race, for example) have done a lot of harm in the modern world. Rather, black pill ideology lies about itself, claiming to show the truth about the world. But as black pillers admit, this is only the reality of ugly or unlucky people. The black pill, far from presenting the “truth” about reality, is actually intensely subjective and personal; black pillers themselves admit that they would not be full of rage and jealousy and hatred had they not lived through what they experienced. Universal philosophy this is not.

This is an experiential and misogynist take on reality relying on a “highly verbally elaborated subjectivity,” as Erin Spampinato notes (Spampinato 2021, 132). And that is what, for all intents and purposes, the black pill ideology does. It reinforces, in the minds of these emotionally unstable and sometimes mentally ill boys and young men, a solipsistic vocabulary and mindset that poses as an “objective,” “rational” outlook about the world, gender, and society, while dismissing and alternative evidence or, indeed, subjectivities as “cucks” or whatever lingo they use these days. It is rather insidious.

One of the key qualities of those that claim to be blackpilled is what I would call “paralyzing powerlessness.” This is where the blackpilled incels will justify to themselves and their audience why they cannot or will not get what they want – and in doing so, come to hate with a passion what they cannot obtain. The powerlessness might from within: depression, a lack of drive, or mental illness; or from outside: poverty, ugliness, or a broken household. This is why we must take it seriously: do genetics not play some part, even if its impact is exaggerated?

This is part of why masculine insecurity does so much damage to black pilled incels: power means agency, means freedom. Powerlessness is prison, with biologically destined misery the only path. One example of powerlessness is a black pilled YouTuber called the Blackpilled Joker. What he believes is not really important here. Amidst all his complaining and ranting, bizarre ideas and neuroses, he becomes the most honest and self-aware in a video titled “twenty five years old never had a girlfriend”:

“I wish I could have had a better upbringing, I wish I could have been a better person, and you know that’s the only thing I can do, wish. Like, I wish I didn’t become this kind of a person. . . .

“I mean, I hope my life can at least be an example for other people. But that’s pretty much, like the last purpose that I guess I can have. Is in hopes for my life, my existence, my story to be an example for other people to NOT turn into someone like me.”

(YouTube)

Incels, in other words, are victims of a tragedy: the “tragedy of a mind, which as George Eliot would put it, has not emerged from its ‘moral stupidity’ and remains taking ‘the world as an udder to feed [its] supreme self long after it should’” (Spampinato 2021, 135). Nevertheless, as the Blackpilled Joker demonstrates, some of them seem self-aware and mindful of the wrecks that they are, but simply have fallen prey to the solipsistic discourse that traps them in their small worlds of mental suffering and hatred for themselves and others.

How can the Buddhist truths liberate someone that has fallen deep down this rabbit hold? How can deconstruction of the self begin when one’s self is all one has to even make sense of one’s failure to meet the masculinity’s demands? This is a herculean task that will need more than a one-size-fits-all solution.

Reference

Ivan Jablonka. 2023. A History of Masculinity: From Patriarchy to Gender Justice. Dublin: Penguin Books

Erin Spampinato. 27 Dec 2021, Hideous Men: David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews in Hindsight from: The Routledge Companion to Masculinity in American Literature and Culture Routledge Accessed on: 01 Sep 2023

Related features from BDG

The Wojak and Doomer Memes: Philosophical and Spiritual Tropes for Gen Z