By Henry Blanke

Henry Blanke is a Soto Zen Buddhist living in New York City. His writing has appeared in Refuse Journal, Speculative Non-Buddhism, Religious Socialism and the Tattooed Buddha. He walks the city in order to experience it.

Roughly nine years ago, I was fired from my job as an academic research librarian. I had held this position for 27 years and the cause of my firing was a growing problem with alcohol. My drinking was an effort to cope with the effects of a major depressive episode which struck me, about a year prior, seemingly out of the blue. After four or five months, my depression lifted, but I was left with a serious drinking problem. Eventually, I began drinking at work and after about a year my library director, who had carried me for this time, terminated me. After completing a 28-day in-patient rehab stint and entering an out-patient counseling program I eventually began a second career as an alcohol and substance abuse counselor. The relevance of this will be made clear towards my conclusion.

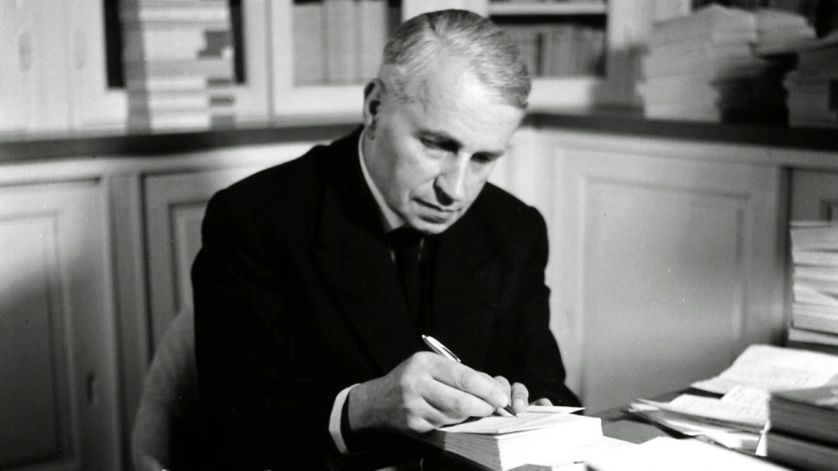

Recently, I have been reading the works of the French philosopher Georges Bataille and am struck by the convergences between his interests in Zen Buddhism, mysticism and transgressive sexuality and my own Zen practice and experiments with BDSM sex. Furthermore, Bataille also had a career as a librarian (as did I in the US) at the Bibloteque Nationale in Paris. It was Batailles’s intention to “blur the lines by [associating] the most shocking, the most turbulent ways of laughing, the most scandalous with the deepest religious spirit.”

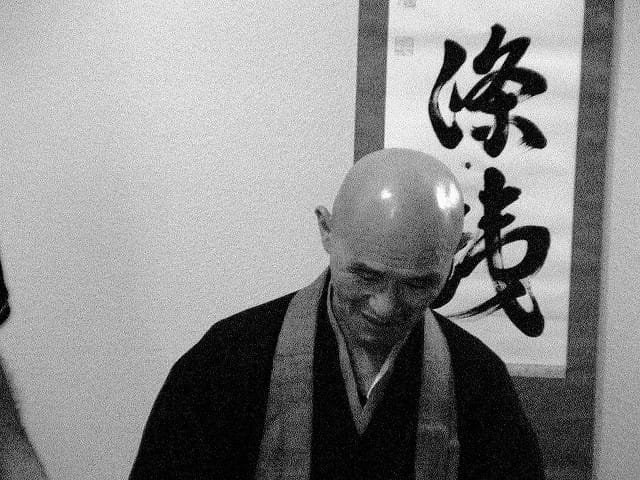

This reminds me of the famously outrageous behavior that historical Zen Masters employed in order to disorient and shock students into awakening. I have a friend who heard a talk given by Hakuun Yasutani Roshi during his visit to the United States years ago. He spoke of Dharma talks given by his own teacher Harada Roshi in Japan. Harada would enjoin his students to be “great Fools” and to laugh with gusto at ordinary happenings.

“Buddha was great Fool,” Harada told them. “He laugh from big belly all the time. [sic]” Now, Bataille might be called a “mystic of laughter” and if you reread his statement on laughing quoted above, you will see that he and Zen Masters both past and current see eye-to-eye on disruptive impact of uproarious laughter.

Furthermore, Bataille’s statement that “human beings are discontinuous in that individuation creates a gulf between the self and the Other,” is in-synch with the Buddhist axiom of no-self and the practical insight of no separation. This is reminiscent of Zen Master Dogen’s famous formulation in Genjokoan: “When you see forms or hear sounds [and body-mind is fully engaged], your body and mind drop away…[and] you intuit things intimately. . . ” For both Zen and Bataille, the Great Matter before us is that before and after death, “the boundaries which separate self and Other be dissolved. The momentary flash of insight (kensho) reveals an impossible state: an identification with everything.”

The enlightenment experience in Zen is akin to Bataille’s breakthrough from profane to sacred which ruptures the psyche. “Such an experience is not beyond expressing. I can communicate it to whoever is unaware of it. [But the] tradition is difficult. The introduction of its oral form is really only barely written,” says Bataille. Compare this with the famous Zen formulation that the Dharma is, “not established in words and letters, [but is] a special transmission outside the scriptures.”

Furthermore, this resonates with the manner in which rituals and everyday activities are carried out in the Zen Buddhist tradition with focused attention and spontaneity. Thus, cooking, washing bowls, making beds, sweeping the floor, and so on become ritualized. In a somewhat similar way, Bataille was concerned with the creation of new rituals. And he set forth ways in which religious rituals and practices expend an energy that, for him, constitutes the sacred. Let us now continue this discussion by looking at the connections between Bataille’s writing and practices of eroticism and transgression.

In another publication, I have discussed the sexual experience of what in the parlance of BDSM sexuality is known as “sub-space.” This is when the submissive participant in a “scene” is induced by the dominant into an altered mind/body state of pain-pleasure synergy. In order to put the submissive into this condition, the “Dom” will use implements such as floggers, paddles, whips, and so on in what is called “impact play.”

As a practitioner of this form of ritualized erotic theater, I can testify to the degree of practice necessary to become adept at the use of these tools and to the skills which must be mastered in order to create a satisfying experience for my partner. For example, while flogging, variations of rhythm and intensity are required as is the proper use of vocal timbre and pitch to create a kind of hypnotic effect. All of this and more is employed at the service of creating a feeling of floating vulnerability for my submissive.

Now let us examine Bataille’s view on transgressive sexuality. “[The world of erotism] . . . is a singular experience. The mind moves in a strange world where anguish and ecstasy co-exist” (think Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa). With this: “We experience the sacred through acts of transgression. The profane world is the world of taboo, while the subject of a taboo, that which the taboo prohibits is sacred.”

For Bataille, the heart if the matter was the ability of sexuality to disrupt identity and transport an individual to their erotic/spiritual limits.

I began this piece by describing my alcoholism which resulted in the end of my career as a librarian and the beginning of a new career as a substance abuse counselor. My job is as a clinician at an in-patient rehabilitation facility in Brooklyn, New York. My responsibilities there included the bio-psycho-social assessments of the center’s clients who were mostly low-income people of color, many of whom had experienced various childhood traumas, as well as the pressures of being poor, Black or Latino and oppressed by a racist society.

I will conclude this essay by drawing the parallels between Bataille’s ideas on the sacred, sacrifice and the dissolution of self; the process of recovery from alcohol and drug abuse; and the practice of Zen meditation.

In my role as counselor at Urban Recovery, I facilitated weekly groups on topics such as the Twelve Steps of AA, intimacy with spouses or lovers during recovery and the bio-psycho-social causes and conditions of addiction. Once a week, I conducted a meditation group and, while many were not interested or too drowsy from their medications to attempt meditation, there was a core group of about five or six who were very much involved. Now imagine this scene: my group, most of whom looked tough enough to eat cars for breakfast, gathered in one area of the floor and sat upright, still and silent for three 5-minute periods. Surrounding us were about thirty others acting out in various stages of anxiety, macho posturing and, in some cases, with the symptoms of mental disorders. My guys formed a kind of insulated bubble amid all the raucousness. And when others would emerge from their rooms shouting or arguing and saw us in silent meditation, they would shut up and keep their distance.

My own Zen teacher, Barry Magid, often speaks of seated meditation as a “container” in that allows the practitioner to experience and work through the various anxieties, neuroses and feelings of failure and inadequacy which may surface during zazen. In other words, meditation provides a safe and controlled environment to examine sources of pain and suffering. Many of my clients told me that they found this idea especially useful since they were experiencing the psychological maladies associated with childhood traumas and substance abuse.

Furthermore, after telling them that the average craving for alcohol or drugs is of short duration, they could see the usefulness of a meditation practice which allowed them to permit triggering thoughts or events to pass. What is more, I would preface my introduction to zazen by likening it to pre-historic humans who would have to maintain a still, silent and watchful attitude while hunting. My hope was that this would appeal to my client’s macho temperaments.

One may well wonder how the process of recovery from the abuse of alcohol and drugs can be connected to Bataille’s writings on ritual, sacrifice, community and inner experience. So let us now elucidate some parallels. The rehab center where I work modeled its approach on that of Alcoholics Anonymous and one of the groups I facilitated dealt with the Twelve Steps. I found that it was difficult for my male clients especially to admit that they were powerless over alcohol. Given their backgrounds, such an admission was often interpreted as a sign of weakness. But since these people were mostly raised as Christians, Step Three’s acceptance of God was much easier.

I should say though that my own experience with AA was less than fruitful since as a Zen Buddhist, I simply could not get past all of the God talk. Bataille often wrote of his interpretation of God as an “immanent power greater than oneself” which jibes well with the view of AA. Furthermore, his interest in the sacred and sacrifice, coincides with AA’s emphasis on service and selfless commitment to helping other alcoholics.

Bataille frequently emphasized that for him writing was an almost contemplative process. Similarly, the counselors at Urban Recovery would encourage clients to “journal” and saw this as a therapeutic aid towards recovery. And finally, in A.A. fellowship is paramount and this coincides with Bataille’s belief in the importance of community.

Bataille’s transgressions, both in his writing and mystical practice, were done with a “religious spirit,” as was his attempt to create new rituals aimed at releasing sacred energy. His advocacy of bizarre and disturbing behavior is reminiscent of the well-known outrageousness of historical Zen masters. The 15th century master Ikkyu shocked his contemporaries as abbot of one of the most important Rinzai monasteries by frequenting bars and brothels wearing monk’s robes. I believe that he was trying to reveal the hypocrisy of his monks.

Bataille was extremely interested in Buddhism and was familiar with key texts. I have foregrounded the confluence of Zen with the work of the “mystic of laughter,” but it would be fruitful for there to be inquiries into the influence of Tantrism on his thought and praxis. Left-handed Tantric rituals involving the heterodox consumptions of meat and alcohol; yogic sexual intercourse; meditating in cremation grounds; and the notorious employment of “crazy wisdom” by Tibetan lamas to shock students out of conventional behavior all seem very much congruent with Bataille’s thought.

Today, Bataille is perhaps best known for his contributions to philosophy and literature, but the intention of this essay was to argue that a deep engagement with mystical praxis informed his life and work. It was by employing the tools of erotism, ritual sacrifice (see the Acephale group), disruptive laughter and East and South Asian psycho-experimental technologies that Bataille’s fiercely transgressive spirit was manifest.