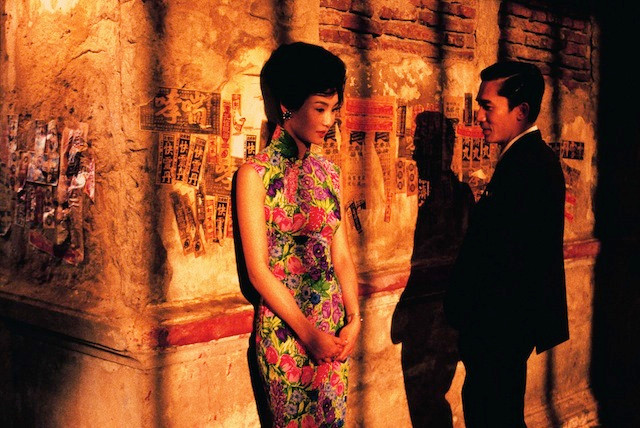

In the Mood for Love did for Hong Kong what La Dolce Vita did for Rome. Just as the Trevi Fountain was relatively unknown as a tourist spot before Anita Ekberg and Marcello Mastroianni’s iconic embrace, In the Mood for Love is a sensuous, colourful masterpiece that eroticizes cramped living spaces and romanticizes the gritty alleyways and crisp fashion of Hong Kong’s 1960s. Perhaps one of the best English-language film analyses I’ve seen is Nerdwriter’s YouTube entry, where he explores Wong Kar-wai’s “frame within a frame” technique (which proliferates throughout the film and makes us feel how “watched” the characters feel even as we are watching them) and, more importantly, how the two protagonists, Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan (played by Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung), upon discovering that their spouses are cheating on them with each other, try to explore how their partners became entangled in their mutual affair.

It’s Chow and Chan’s way of dealing with the pain of being cheated on, but by embodying the other’s spouse, and role-playing scenarios of seduction and betrayal (sometimes it’s not clear which role they are playing – themselves, or the other’s partner), they not only manage to avoid the necessity of confronting their own partners and dealing with the fallout, but also flee from their budding affections for each other. Granted, there are hints of the suffocating social atmosphere of the sixties: the constant gossiping of the neighbours, the assumptions held for the role of a wife or husband… Yet this failure to face reality in a clear-eyed manner, and the almost masochistic way in which they avoid consummating their love simply because they think they are somehow better by enacting the fantasy of their spouses cheating (as opposed to their spouses actually cheating), is terribly self-deceiving.

We all create fantasies to bandage over painful realities that we wish to avoid dealing with, but such fantasies can be perverse and keep us from confronting the reality that we originally created these fantasies to distract us from. In The Mood For Love hits home because many of us, in times of unhappiness or misfortune, have constructed narratives of our own powerlessness and innocence. Were Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung not such beautiful people, Wong Kar-wai noted, we’d be less sympathetic to the dark psychology of their characters. As Nerdwriter points out, it is when Mr. Chan finally confesses what both knew, that they were in love with each other, that the edifice of innocence they’ve so painstakingly erected collapses, leaving them with nothing but the brute reality of having ceased to become an object of love for their spouses.

The most infuriating part actually comes after this realization: rather than seeking separation from their current partners, to whom they mean nothing anymore, and getting married or at least resolving to be together, they just continue to miss each other, at several moments in the movie, the last time by moments. And all that’s left for Mr. Chow is, rather pathetically, to whisper his secret in the hole of a temple complex in Cambodia, observed silently by a young Buddhist monk.

How long will we continue to create fantasies that allow us some space to flee from the painful truths we encounter every day? More importantly, what will we do about these painful truths? Will we face up to them? Or will we doom ourselves to continuing to run away from them by other means, just as Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan did?

Perhaps refusing to see reality is just part of the samsaric human condition, which is why we find In the Mood for Love – itself a fantasy, a movie – such a safe medium to remind us of the lengths we will go to delude ourselves. To deny ourselves the closure, possibilities, and happiness we really deserve.