Antiquities and Numismatics

When I was a student of Buddhist Studies at SOAS, numismatics featured prominently in the dating of Buddhist history and associated sites and artifacts. I had not even heard of the Bhamala Buddhist Complex ten years ago, but this site in the Taxila Valley is no exception. The first expedition by Sir John Marshall in 1930–31 had dated the monastery and stupas to the 4th to 5th centuries AD. But the groundbreaking third expedition by KPDOAM unearthed 14 copper coins dating to the 3rd Century. On these coins are engraved the faces of Kanshika II (200–222) and Vasudeva II (c. 275–300), kings who never quite reached the height of success as their predecessor Vasudeva I, or the Buddhist piety of Kanishka I. Radio carbon dating of sampled antiquities unearthed at the site during the second and third expeditions also range from the 3rd to 4th centuries. This means that the site of Bhamala was, at the very least, economically active and accessed concurrently with the era of the Three Kingdoms in China, and the Crisis of the Third Century in the Roman Empire.

The first excavation’s haul constitutes more than 100 valuable coins from the 4th to 5th centuries AD, with an inventory of:

- 5 copper pieces of Vasudeva I,

- 1 copper coin of Kushana II,

- 1 silver coin of Bacharana, which was later on attributed to Kapunada by Gul Rahim Khan,

- 1 copper Indo-Sasanian coin, and

- 21 silver coins of the white Huns.

Some 30 pieces of stucco sculpture, mainly detached heads of statues, were recovered from the cruciform stupa’s court. Among the stucco, panel there is a partially preserved Parinirvana scene.

The second excavation yielded a total of 73 objects, including clay and terracotta sculpture fragments, door fittings, iron nails and copper coins. The expedition’s most important finding was a carnelian seal depicted with Gaja Lekshmi, an Indic goddess, with two children and elephants.

2014–15’s expedition saw the largest haul of items. During this season, a total of 513 registered objects were reported, which include 3 stone objects, 1 wooden object, 20 copper objects (copper coins number at 14), 97 laminated steel and iron pieces, 94 stucco objects, and 295 terracotta objects and a large number of potsherds.

Stupas

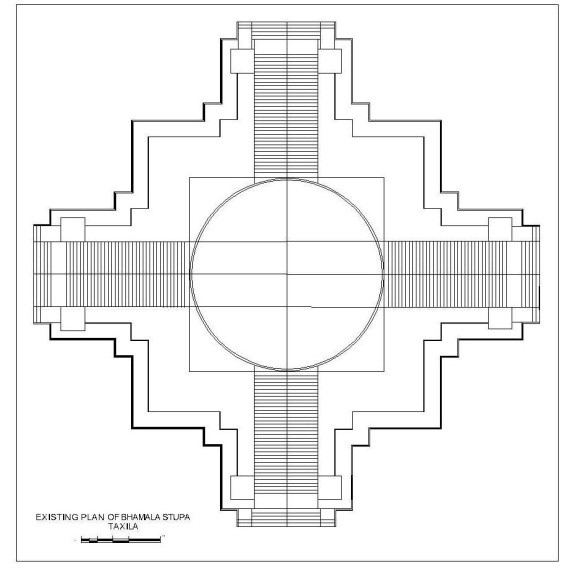

Since the earliest days of ancient Buddhism, the expression of Dharma decades or a couple of centuries after the Buddha’s death (I prefer to call it pre-sectarian Buddhism), stupas have been vital components of Buddhist sites of pilgrimage and devotion. The Bhamala Buddhist Complex hosts two such stupas: the so-called “Cruciform” Stupa A, which was discovered during the first expedition, and Stupa B, which was partially excavated during the third expedition.

The southern and southwestern sides of Stupa B are sadly severely damaged. The upper portion of the stupa up to the podium was also found missing. In contrast, KPDOAM found its northern and eastern sides in a better state, with chapels on the eastern side. The lower part of the stupa was once covered in lime plaster, and stucco sculptures surrounded the stupa’s perimeter. Traces of the lime plaster and stucco fragments of sculptures have been found.

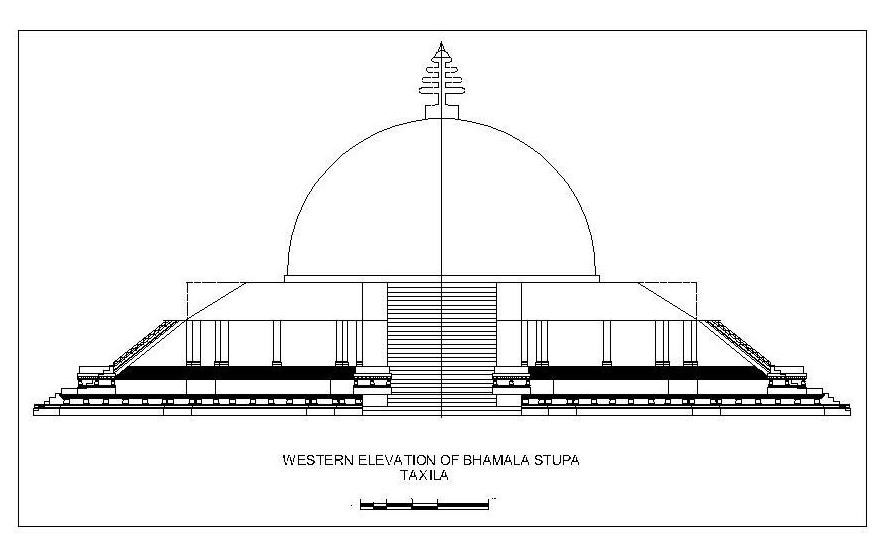

Stupa A, the Cruciform Stupa, enjoys a very rare design. It still has an elevation of 30 feet in its ruined condition, meaning that its tall square plinth and four flights of stairs (corresponding with the four directions) are extremely tall. There is also a dharmachakra design at the eastern flight of steps. (Marshall 1951:394) The podium is 9 feet high above the plinth and was relieved by Corinthian pilasters with small stucco figures of the Buddha. It is theorized that a circular drum and dome and umbrellas would have been built above the podium. The drum was probably decorated with figural sculptures, as there is one draped figure from the stucco relief on top of the podium.

The center is built of semi-ashlar masonry and heavy blocks of limestone with small stones and mud filling, which are common characteristics of 4th to 5th century architecture. There are several figures of Buddhas on bays, and the cruciform stupa is surrounded by 19 votive stupas. Soft Kanjur stone was used for moulding the plaster, with a thick face of lime applied on most of the architecture and figures festooning it. The projecting podium is decorated by a series of panels separated from one from another by poorly designed Corinthian pilasters (why they were rushed is not certain).

Some panels remain bare while others have Buddha images (including the Parinirvana scene), triple Buddhas, and the Buddha in the dhyana or siksha mudras. Other pieces of Kanjur stone, such as a lion head and pieces of an umbrella, were also reported.

Monastery

The monastic establishments at Bhamala are located to the east on the stupa, and were excavated during the first season. The monastery is built in the late semi ashlar kind masonry. As usual, the interior walls were covered with clay plaster, much of which was converted to terracotta after a great fire (perhaps by earthquake or perhaps by malign conduct) destroyed this structure.

After the first season’s excavation, Sir John Marshall gave the detailed description of the Monastery, which is discussed as below:

In planes the cells are standing up to the height of 10 or 12 feet and in one of the cells (no 6—7) the door way including the stone work over the lintel, was exceptionally well preserved, but the windows, which for safety’s sake were invariably placed near the roof, have all disappeared.

(Marshall 1951:394)

And:

Outside the north wall and near its middle, is what at first site looks like an unusually massive buttress (Pl. XVII), but was more probably that base of a watch- tower similar to the one on the north side of the monastery G at the Dharmarajika. But there is also a true buttress (Pl. XIII) at the north-east corner of the monastery, which was once evidently in danger of collapse. Both the watch tower and buttress are built of same kind of masonry as the main body of the structure, and must have been added at no great length of time after its erection. The monastery to the east is designed on the usual plan with a large court of cells in front, and an assembly hall, kitchen (D) and refectory (E) in the rear.

(Marshall 1951:395)

Before, finally:

There are two exceptional features in this monastery. One is that the veranda (Pl. XIX) along the western side of the court of the cells is a broader than typical ones, and there are two extra cells on two corners of the veranda such are not found in other monasteries. The other exceptional feature is that the only flight of stairs giving access to the upper floor is located in the kitchen instead of in one of the chambers of the court of the cells, though it may be that there was a second flight in then court of the cell which was made of wood and has perished.

(Marshall 1945: 394–95)

We are incredibly fortunate to still have these remnants of the site available to us, despite the complex partially wrecked and gone. This is why the work by the KPDOAM is critical: digitization will not only preserve forever the physical remains, but can also help us detect what might still be waiting to be discovered and saved.

This article was written in collaboration with the Digital Heritage Center of the Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPDOAM)

Reference

John Marshall. 1951. Taxila: An illustrated account of archaeological excavations carried out at Taxila under the orders of the government of India between the years 1913 and 1934 in three volumes. London: Cambridge University Press.