By Belén Boville

Belén Boville is a journalist and writer. She is a Soto Zen Buddhist nun ordained by Master Barbara Kosen

The property bought by Michel Tei Hei’s Zen Sangha belonged to a local Cuban bricklayer who emigrated to the United States to improve his life and prospects. A few months after selling it, the man came back to repurchase it; he regretted having sold it, it was his “paradise” and he had come to a life that was his “hell.”

Many people leave Cuba, especially the young, thinking of a future with more opportunities in other countries, particularly in the “free” Western world of consumption. Michel laments that some Sangha people who commit themselves and are ordained as monks or bodhisattvas end up leaving for Europe or Canada, the United States and Mexico searching for more professional opportunities and a more financially viable future.

For those who remain, the dojo and the practice of zazen and the Way, are a refuge, a support in difficult times; a community of mutual help where interdependence becomes increasingly valuable for daily survival and connection. At least they will eat well during the sesshins, says Michel, as he opens the suitcases and discovers their contents.

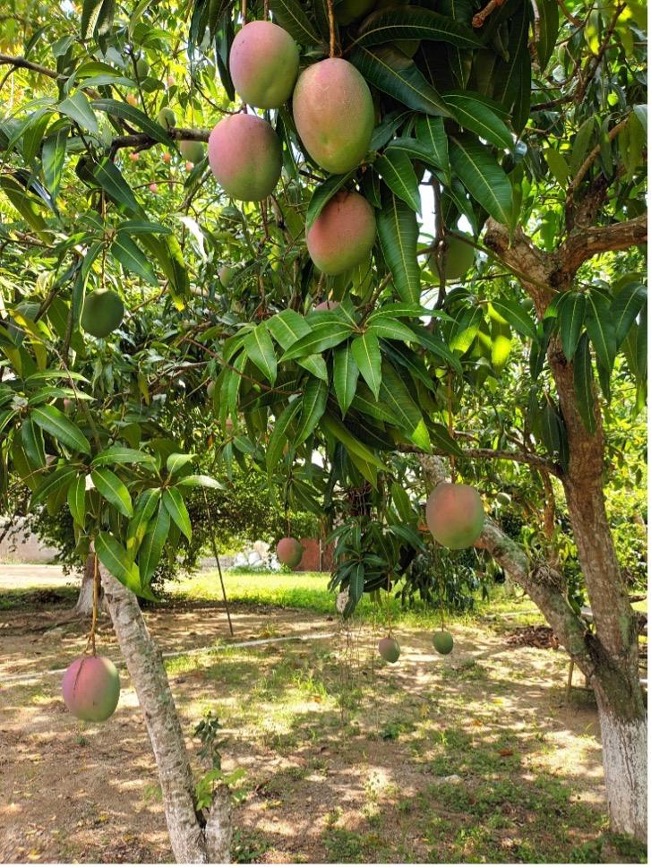

The land is an orchard, and in addition to the original trees, they have planted a vegetable garden with carrots, pumpkins, onions, chillies, and sweet potatoes . . . they are practically self-sufficient. We have brought them many packets of seeds and foods that do not spoil and are rich in vegetable proteins and nutrients, such as beans, lentils, chickpeas and soy, olive oil, and tomato concentrate.

Little by little, more and more members of the sangha began to arrive. The journey is long and complicated, even though they are only 20 kilometers from Havana. My travelling companion, Gustavo, a Spanish-Argentinean monk, has hired a minibus, and they all arrive in droves, young and old, because the two daughters of Andrés, the monk, and his wife were also coming. They were young men and women, the oldest about 40 years old. They were all thrilled to meet the members of the Spanish sangha, although Gustavo was an old acquaintance and the promoter of this new temple in Cuba. Those coming from Matanzas (only 120 kilometers away) or other parts of the island arrive the next day, after a 15-hour journey combining several buses and dead hours.

The neighbours look after some cows, the cows of the revolution, well, of the government. Yoni knows all about cows, but they only eat grass and don’t feed them because it’s too expensive now (since it comes from Ukraine). The cows are flaccid, and starving, and almost all of them are anaemic. In Cuba, as in other parts of the world, there has been a prolonged drought. Although it rains in the afternoons now, there have been months without a drop.

There is no hunger in the countryside; there are people with chickens and pigs nearby, although everything is very much under the control of the community because everywhere there are “political commissars” who report on their animals and all activities in the countryside (and in the city). Cubans are not used to or have no tradition of gardening, as fertile as their island was, few people cultivate a vegetable garden, we are the exception. The orchard is life, insects, birds, flowers, and lots of fruit at any time of day, delicious mangoes in midsummer, juicy and sweet, and guavas or plums. To eat fruit from the trees is to reconnect with everything, with nature and the primitive being we still carry within us; a great pleasure and privilege.

Sleep is deep. Each room has a powerful fan to cool you down at night. The rooms are simple, but we sleep in beds, with clean sheets or mats, and we have a full bathroom for washing up, with running water, showers, and toilets. Of course, here, as in almost all houses, we wash ourselves with the Cuban shower: with ladles of water (warm or hot) from the bucket we have filled. It is a simple way of life, without excesses, back to basics, without desires beyond what is strictly necessary, a good practice for Europeans and North Americans who come from countries of relative opulence.