The Centre for Spiritual Progress to Great Awakening is one of the largest Buddhist centers in Hong Kong. Located in an industrial building in Kowloon Bay, it spans three large wings, each several thousand square feet. There is a sizable office section with meeting rooms and working spaces that are as well-equipped and appointed as any small business, a colossal storage room, and finally the main Buddha hall for religious practice. At the head of this organization is Ven. Chuan Deng, who noted that this venue was made possible thanks to a stroke of luck from a generous donor. “When we opened our first center in a different neighborhood (Lai Chi Kok), we had little over a thousand square feet. Now we have over 10,000. This is a multi-function place, a basket of many plants.” It is a serious environment that aims to achieve serious things – and there is nothing more serious than death and this undeniable, inevitable milestone of the human experience. It is the reason why religion exists.

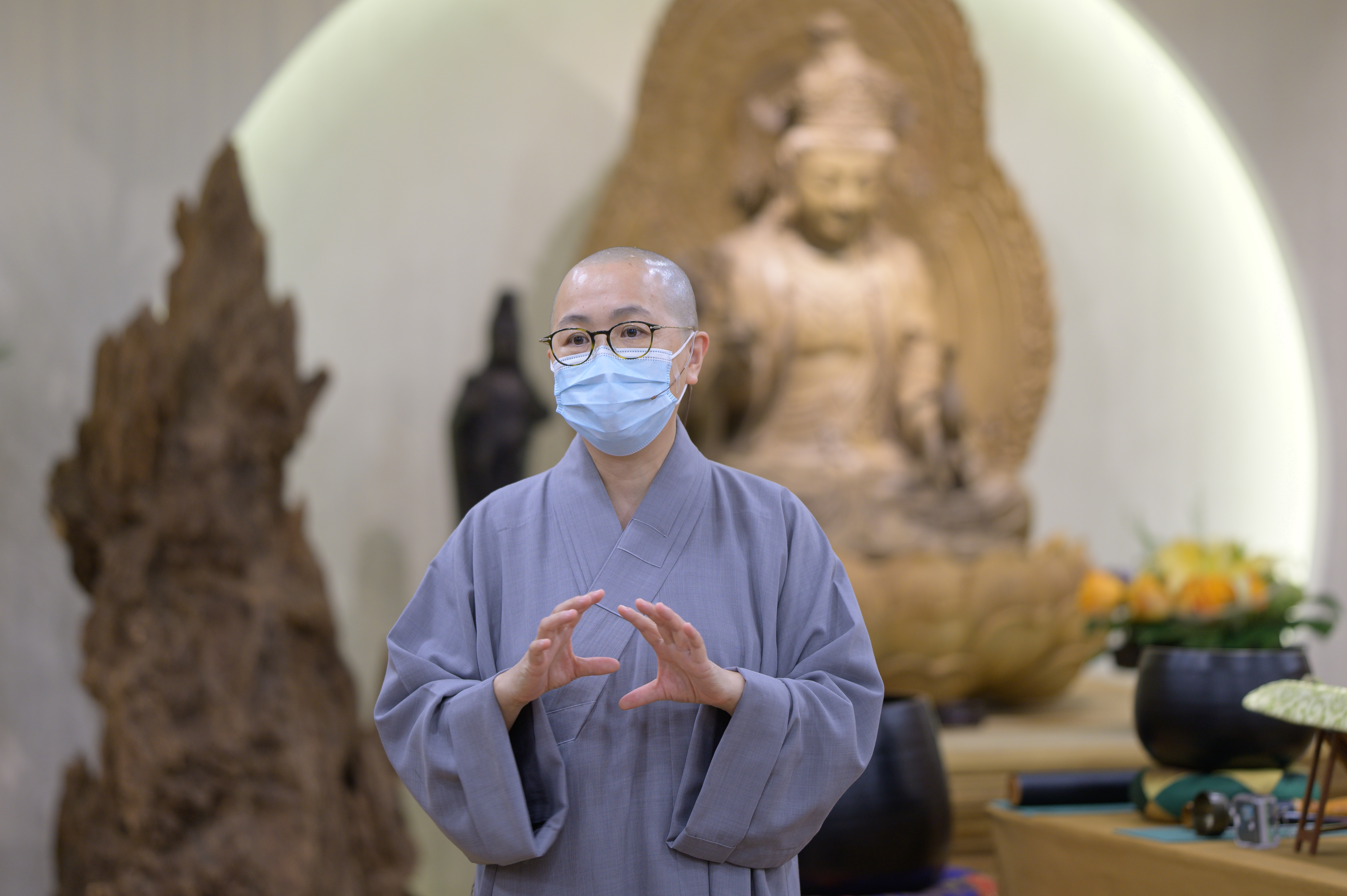

Ven. Chuan Deng took refuge when she was 21 years old in 1995, and in 2003, at age 29, took the monastic vows. While she had always been drawn to the vocation of a bhikkhuni, it was a different story with how she came to become a pastoral minister for the dying. “It has all been according to karma. I never had a plan to set out on this path, since monastics usually want to stay at the temple. But by a twist of fate, I was inspired by Ven. Yin Yeung, who was part of a lineage of pastoral care that can be traced back to her own preceptor, Ven. Sheng Yi.”

The connection with Queen Mary Hospital (QMH), one of Hong Kong’s largest and most important public hospitals, was critical. “In 2009 we launched the program with the view to train 8 to 10 volunteers,” she told me. Since then, the program has now expanded to 16 hospitals. The original volunteer pool, numbering less than a dozen, has exploded to over 350 well-trained volunteers, designated “spiritual envoys” by the organization, and there are 12 Buddhist chaplains, both lay and monastic.

“At first, I started by accompanying Ven. Yin Yeung to see patients. I learned to observe and listen,” said Ven. Chuan Deng. She was tasked with continuing the tradition of hospice care in Hong Kong when her teacher no longer had the time. In 2011, she set up a Buddhist chaplaincy unit, and hence began a new tradition of honorary chaplains, who needed a decent grasp of Buddhist philosophy and practice.

The act of listening and attending to the dying – and guiding them sensitively to help let go of themselves and each other – is a delicate art. The traditional aspects of religious education, such as understanding how rebirth works, the Bardo realm, and karma are standard requirements. However, a new level of emotional intelligence is demanded in the competent pastoral carer. Tactfulness is required, but at the same time, one must be fearless with the truth. Rebirth, after all, is samsara, in which there is perpetual suffering. “It’s not just attachment to this life,” says Ven. Chuan Deng, “but the fact that the volatile and desperate feelings of the dying’s loved ones can be hindering a smooth passing.” The pastoral carer’s ultimate goal is for the family to experience acceptance and be at peace.

Ven. Chuan Deng has noticed some interesting trends. For her, death is still a taboo in society because there is a lack of exposure to the discourse of pastoral, palliative, and end-of-life care. She advises that misperceptions need to be corrected. Funerary rites are no longer the be-all-end-all of Buddhist care, with the preparation for death being emphasized as a process that can encompass the entire remainder of an ill person’s life. Quality of life, a sense of meaning, community, and most importantly, being able to define oneself and live on one’s own terms is critical. “We are not our condition or disease,” says Ven. Chuan Deng. “We must not be attached to dying, but we also do not need to cling to what afflicts us.”

There is also the question of visitation. So-called “tele-care” is becoming more common. Pastoral visitations might no longer be at the hospital. “Most people would prefer their loved ones to be at home. So, if the doctors allow their close ones to return to a caring environment, it would seem natural for the minister to prepare accordingly.” Whether at home or at the hospital, Ven. Chuan Deng emphasizes that any program needs five things: care for the whole person, the whole family, the whole team, the whole process, and the whole community. Talks, shows, and activities also herald a dawning era of community-based pastoral care. “If we can correct misconceptions and help people to face their loved ones’ ends productively, some will even return as volunteers to continue our work. They appreciate what we’ve done for their own families.”

Traditional models of care for the dying will not be dispensed with completely, but rather change and diversify based on the extremely disparate circumstances and unpredictable predilections of patients and their families. “When you’re sitting with the terminally ill, you can feel the grief of not just the sufferer, but also their immediate loved ones.” It is the pastoral carer’s burden to nudge them toward acceptance, and even then, any hint of heavy-handed guidance or impatience can be a fatal rupture of trust.

“Dealing with attachment productively is one of the biggest questions facing Buddhist carers. In my view, the only way to accomplish this is to change people’s frame of reference and revise their assumptions. This can be intellectually and emotionally challenging. They have to be open to doing this in the first place. Otherwise, they will live with all kinds of regret, and regret is very debilitating. Yes,” she affirmed, with a smile of conviction: “To have no regrets. . . that is what matters.”